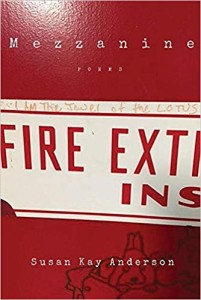

Mezzanine is a quietly powerful collection of important poems about the American West. These stories and questions are written in a woman’s voice, with whispered insights that  sometimes tickle the ear like the buzzing of a bee’s fragile wings. Susan Kay Anderson portrays a land still rife with mystery and possibility, despite tragedies and losses. If you are at all familiar with the American West or have wanted to know more about it, climb up to the mezzanine, where the view extends beyond the landscape into the past.

sometimes tickle the ear like the buzzing of a bee’s fragile wings. Susan Kay Anderson portrays a land still rife with mystery and possibility, despite tragedies and losses. If you are at all familiar with the American West or have wanted to know more about it, climb up to the mezzanine, where the view extends beyond the landscape into the past.

In this collection, everything gleams with the poet’s imagination, like the Baerenschliffe (bear shimmer) she imagines coating the floors she mops in the opening poem “Fire Cipher.” In the title poem, the poet inhabits the space between floors of a university building, between day and night, between the real and the imagined, between the detritus of the work day and the silent majesty of public art. Dreams and memories drift through this space and the reader realizes that this is what we do throughout life, telescoping out of the past to zoom in on the all-too-present. By the end of the title poem, we can agree with the poet that “In the aftermath of nothing, I’ve found a little something.”

The poet’s inner life is rich with voices, memories, insights—from childhood to the present, voices of the dead and missing speak to her. The question that asserts itself throughout the book appears:

“Was it two minutes ago or was it ten years?

Was it half a century ago

or was it last year?”

Bittersweet observations draw us in, as the poet touches on our deepest hidden vulnerabilities: “The leaves look back to their trees wanting more chances.” Who hasn’t felt that? And that desire for redemption comes with a promise we desperately hope is not futile: “…if you/ planted me here/ …/ I’d bear fantastic fruit.”

Some poems start without titles, and some end with a resonant note that hangs in the air. Woven through each are arresting visuals like this one of the moon: “She is astonished. Her bombed face a perpetual O.”

The book’s final poem, “Man’s West Once,” has its own mezzanine built of other authors’ voices. It, too, is “a place to look up, out, and back.” From that space suspended between the poet’s own words, we can see the bottom and top floors, stages for scenes and characters from the poet’s earlier lives in town and villages across the Great West. The book’s real triumph, however, is not its reflective cataloging and assessment of a life spent searching for what was “man’s west once.” It is that a book has been written about the American West from a woman’s perspective, and this one is alive with indigenous voices and native wisdom. That instead of the violent pillaging of a gold rush or a cowboys-and-Indians Hollywood shootout, the landscapes are lovingly preserved, so even delicate butterflies and bees have their say. And the trees and lakeshores, forests and rivers are populated with bears, owls, and wolves. The dangers and mysteries come from these original inhabitants of the west who, under the poet’s watchful eye, get their long overdue homage.