Pardon my horrible headline, but I have been in shock since watching “Oppenheimer” last night, reading the many recent articles about the man, the movie, and the overlapping of the man and the movie. I’ve been sucked into the vortex of his story, which is really our story, whether we know it or not.

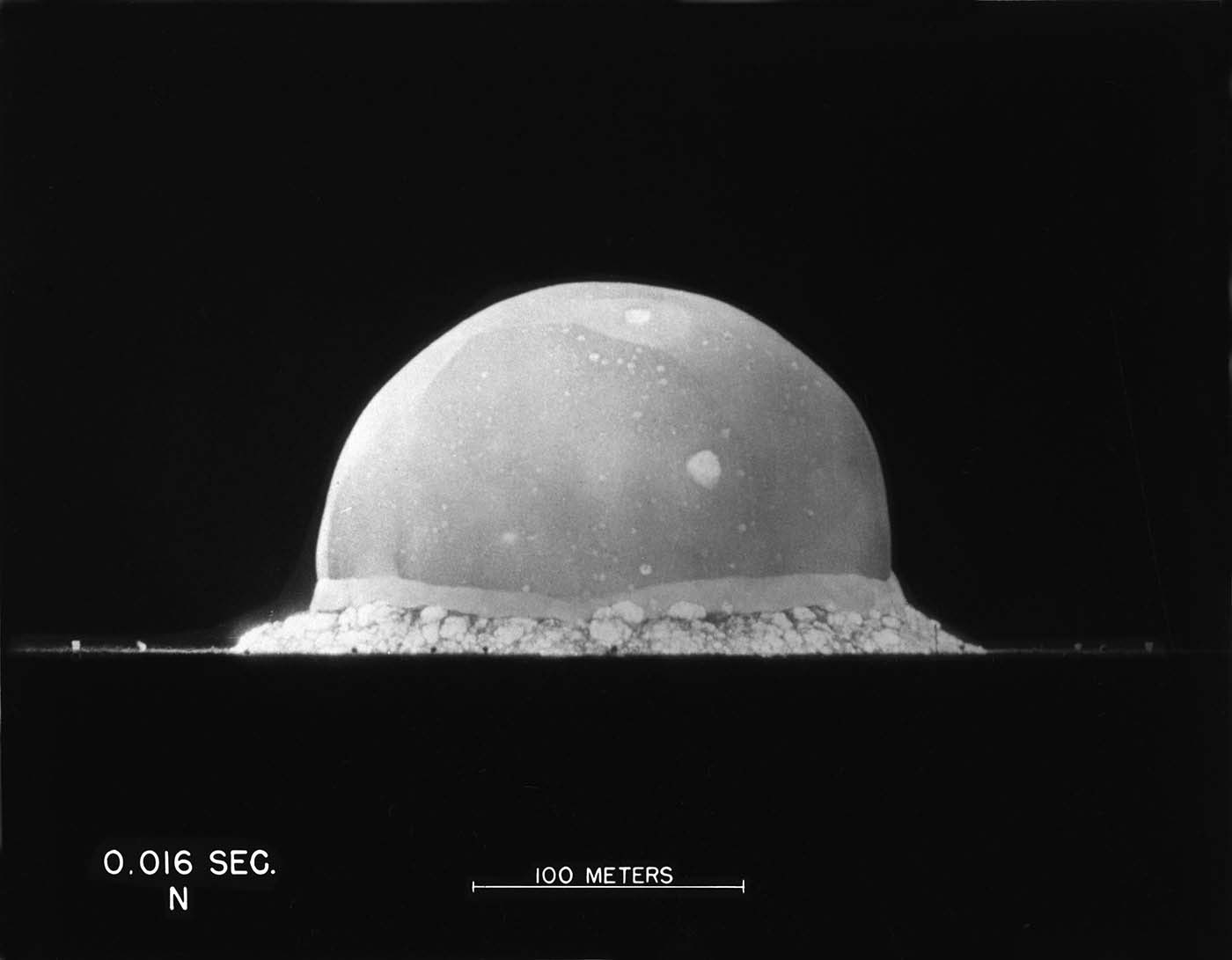

A view of a nuclear blast you don’t often see. This was the Trinity test of “the Gadget” at 0.016 seconds. It almost looks like a jellyfish. An innocent, deadly jellyfish. Photo: atomicarchive.com.

This is not new territory for me…I’ve been reading about the atomic program and living with its fallout (bear with me) since I was eleven years old. So it is not just with admiration of the film that I jump on board…it is with a heavy heart.

Let me tell you a rambling, webbed story that reaches no conclusion…it puddles and spreads and eventually seeps into dry desert sand, except when it doesn’t and instead comes roaring back like a second shock wave.

My father was a geologist. He worked for the Atomic Energy Commission (formed to develop the A-bomb) in the early 1950s after getting his M.S. at the University of Albuquerque in 1952. He married my mother that summer. In his first job, he inspected uranium mines. Soon after, he began his work as a copper exploration geologist. Copper is found in deserts, so he dragged my mom and a succession of kids through Utah (where my oldest sister was born), Libya in North Africa (where my other sister was born), Arizona (where I was born), until we settled in Littleton, Colorado. My brothers were born along the way in California and Michigan. So there was a lot of moving. Like, yearly. With a summer in Montana living in a trailer. Also, some time in tents. Yes, I love road trips and camping.

While we stayed home with Mom, he spent summers in the desert, sometimes downwind of old nuclear test sites. We suspect his death from an aggressive lymphoma at age 46 could have been caused by nuclear waste exposure. Will we ever know? No. But we know. I was eleven when he died. It was like a thermal blast in slo-mo. But here we are. Patchy on the outside, achy in the bones.

So I not only lived through much of the Cold War, I was obsessed with it.

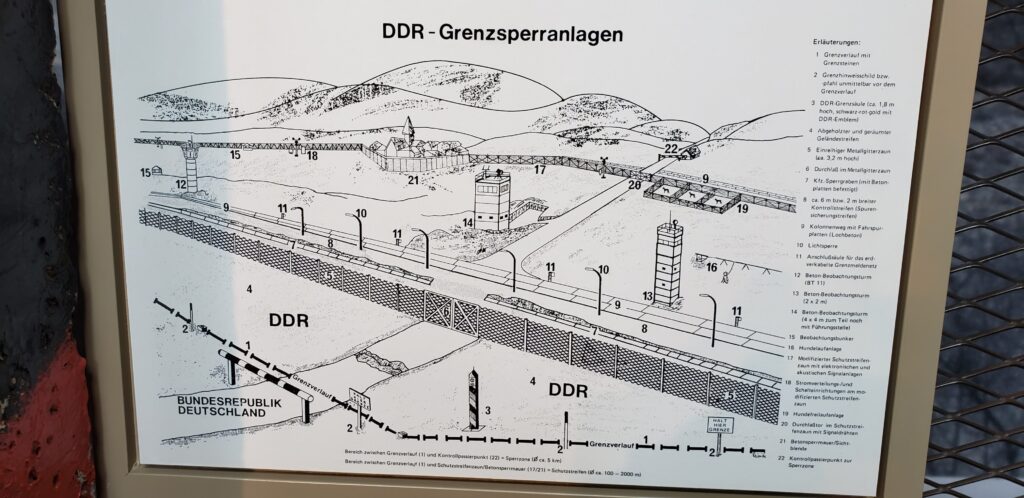

Section of fence and a border post that once divided East Germany from the West, displayed at the Tränenpalast in Berlin. Photo: Sandra S. McRae, May 2022.

After my bachelor’s, I got a Fulbright grant to study in Germany, and landed on the border between West and East Germany, at the University of Göttingen, where Oppenheimer got his PhD in physics. I didn’t know he had been at Göttingen until the university was mentioned in the movie, but you see how we’re now at the webby part of the story. (I also just learned his brother, Frank Oppenheimer, had taught at CU-Boulder, where I got my graduate degree.)

Living 10 km from the border with the German Democratic Republic, with its mine-laced No Man’s Land, fences, and machine guns, it was impossible to not think of “mutually assured destruction” in the late 1980s. First of all, I had friends with families split by the Iron Curtain. I stood flummoxed at the Berlin Wall, wept at Checkpoint Charlie, and had several extremely uncomfortable experiences crossing German-German borders. (The East German border guards were flirt-proof, which was scary. When I had flirted with Russian guards in Kyiv and Leningrad and Moscow, I thought there was hope for democracy yet. Well, flash forward to 2023, and it’s a teeter-totter, isn’t it?) Plus, any nukes fired from the US or the USSR were going to cross right over my head in Germany. Let’s just say yes, I did have vivid nightmares, and often.

The many layers of threat that made up the Iron Curtain. Display at the Tränenpalast in Berlin. Photo: Sandra S. McRae, May 2022.

Watching the movie not only dredged up that old existential dread, it reminded me how much time I’ve spent researching bombs, the Cold War, fallout, half-life, and more. Not to mention how deeply atomic metaphors have permeated American speech. Now, I have been criticized for having a bit of a dark streak, but folks, it’s only because I pay attention. Here’s a short list of why this stuff has puddled in my mind:

- For most of my life I have lived on either side of Rocky Flats, a Superfund site where they made plutonium triggers for nukes until it was closed in 1992. I spent some time with the Rocky Mountain Peace and Justice Center in grad school.

- Some of the ills associated with the above include the high levels of radiation still underground at Rocky Flats, where new homes have been built and sold nearby. A friend who grew up downwind of Rocky Flats had thyroid cancer, and his mother and aunt who also lived there died of cancer.

- Radiation is literally background static in Colorado’s Front Range, where you need to test for radon when you buy a house, so people get complacent.

- I have spent most my life near I-25, dubbed the Nuclear Highway by activists because it runs past Minute Man silos in Wyoming; the Rocky Mountain Arsenal, Rocky Flats, Cheyenne Mountain (home of NORAD), and the Air Force Academy in Colorado; and Alamogordo—home of the Trinity site at White Sands Missile Range—in New Mexico. Oh, don’t forget the little town of Radium Springs, named for the high levels of radium in its waters, touted as beneficial and healthful. Cheers!

- Driving to White Sands National Park in the 1990s, I photographed many businesses enthusiastically named to welcome Ronald Reagan’s (failed) Strategic Defense Initiative, dubbed “Star Wars.” How many Atomic Cafes does one town need, really? I met Carl Sagan when he came to Colorado State University to speak out against Star Wars because he felt it would accelerate rather than decelerate the arms race. But locals near White Sands Missile Range saw big money coming to town, so they were enthusiastic. Which reminds us how the nastiest stuff will be glossed over with a shiny wrapper if someone thinks they can cash in on it.

- We grew up with a chunk of uranium ore in my dad’s mineral display cabinet. After some internet research, I think the risk of getting sick from it are pretty mild, unless you eat or breath the dust, and I doubt my dad would’ve put us at risk. It was behind glass, anyway. Staring over my shoulder as I learned to type on my dad’s old Olympia typewriter. No wonder I’m a poet.

- Reading about nuclear proliferation is one thing, but this map of all the nuclear detonations from 1945 to 1988 teaches us visually. I wonder if anyone is counting nuclear testing’s contributions to global warming. And who considers the cost to the planet in other ways? Think of the sea life and animal life sacrificed to these tests.

Message to Putin from the Checkpoint Charlie Museum after he invaded Crimea. Photo: Sandra S. McRae, June 2017.

- I have studied nuclear warfare more than I have written about it, and one of my favorite sites is atomicarchive.com/. The Media Gallery is a must-see. It pains me to think younger generations might not be aware of what is still a major threat to humanity (see Russia’s War on Ukraine et al, 2014 to present). Which is why I’m grateful for this movie.

So here we are, where we started. If you are hoping the movie includes a fulsome debate on the implications of the use of atomic weapons, that happens mostly in Oppenheimer’s head. The governing idea of the time was “better that we do it before the Germans or Russians do” (perhaps they were not wrong) and the movie portrays that mentality clearly.

And to be fair, NOBODY knew exactly what the hell a nuclear bomb would do—but again, that moral reflection pond was shallow in 1945, under pressure to beat the enemy (and our Soviets allies) to the punch. We can and should talk about a full accounting of the horrors we unleashed on Japan. To start, we should all look at the pictures as adults, now, and every year in every classroom–to teach our children to fully consider possible outcomes, including oversights and errors. We should always strive to consider the unknowable consequences of our policies and decisions, as Oppenheimer did and tried to get others to do. That was the big piece he kept trying to put into place: to study our actions through a moral lens, a practice which has fallen out of fashion in our immediate-gratification culture.

The US has never offered reparations to the hibakusha, even those who were US citizens in August 1945, which is a serious moral gap in my opinion. Japan has backed off on support for their progeny as well. So it falls on each of us–in our daily lives, in our civic engagment–to mindfully address the little, dehumanizing hatreds that can build up, like a bomb in slo-mo, so they don’t create devastating explosions and regrets.

The movie, of course, doesn’t go there, nor does it have to—it does plenty in three hours. But one thing it really highlights visually is how a monoculture can lead to a brilliant (I fully intend the pun) leap forward–in this case a monumental win for theoretical physics. But it can also convince everyone in charge that a terrible, horrible, god-awful concept is the very best option. You’ll have to watch the movie to the end to see what I mean.